Climate change has hit each and every part of the world adversely in a direct or indirect manner. For India where more than 70% of the population depends on water from rivers and rains, what has become more important is the need to address the impact of climate variability and extreme weather events. Water resources development is approaching or has exceeded sustainable limits. More than 75% of water that flows in rivers is withdrawn for agriculture, industry and domestic purposes. This has led to the approaching physical and economic scarcity of water all around the country. It is expected that the availability of water in our country is likely to fall down to 1,140 cubic meters in 2050!

In between all this stream of portentous events, Mr. Rajendera Singh also called as “The Waterman of India” ignites a lamp of hope in the field of water conservation.

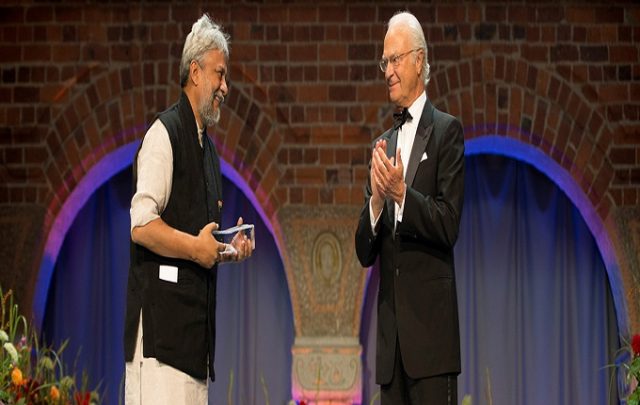

He has put his relentless struggle to revive indigenous wisdom on water harvesting and management systems and has passed it on to those who have long forgotten it. “Water is my life, my happiness, my teacher,” he says. Included in the list of “50 people who could save the planet” by The Guardian Rajendera Singh has won the Stockholm Water Prize, an award known as “the Nobel Prize for Water”, in 2015, Jamnalal Bajaj Award in 2005, the Magsaysay Award for community leadership in 2001 and many more. Born in 1959 his birth place Daula offered him good access to highest quality water in his childhood-the water of Ganges.

In 1974 a member of Gandhi Peace Foundation visited his place and talked about issues related to village improvement, cleanliness of the villages, open libraries for the mass that tickled Rajendera’s mind and was an eye opening event for him. The emergency of 1975 made him realize various notions of democracy that persuaded him to follow Jaiprakash Narayan’s motto of ‘Total Revolution’ and join the Chatra Yuva Vahini. According to him community is everything, so after completing his education he served as a National Service Volunteer in Jaipur and also joined the Tarun Bharat Sangh (TBS) an NGO founded by professors of University of Rajasthan. “In the 70 years since independence, more than 10 times more land is under drought and 8 times more land is under flood. I have seen people in some of these villages being displaced three, four, eight times. This is not really development”, increasing frustration and dissatisfaction towards the developmental authorities led him to quit his job in the year 1984. Leaving their families behind he with a group of other four set out for the last stop into the interiors of Rajasthan.

In the “dark zones” of Alwar district he found out that there was no river but only a path of rocky barren surface present which was later rejuvenated by him into a perennial river with the help of ancient traditional johads – earthern check dams. Over the consecutive years the modernized digging of borewells deeper and deeper into the earth has not been proved appropriate for the ecology of fragile Aravalis and has futher has led to lowering of groundwater table in the area. He learned the indigenous techniques of old check dams from the villagers and started a padyatra in order to educate other villagers and rebuild the same. Rajendera’s continuous efforts led MoEF to release legal notice to ban mining in the Aravallis that inturn led to rise in the water level of lakes near Sariska. The building of 115 earthern and concrete structures within the sanctuary and around 600 in the periphery led to Aravari become a perennial river and win the “International River Prize”. A clear picture of sustainable development is seen by his efforts along with the village communities in the western and central India including the states Rajasthan, Gujrat, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra.

Uncountable initiatives like rainwater harvesting, building up of Bhairondev Lokk Vanyajeev Abhyaranya (People’s Sanctuary) for reforestation and forest conservation, Pani Panchayat for traditional water conservation wisdom taken up by Rajendera in various villages has encouraged villages to grow into sustainable communities. He has also acted as central key in various controversial projects related to dams in our country where he makes a firm point that every project must be reviewed after 20 years.

He believes in the idea that the old–school water management techniques enable development without leaving scars of destruction. And the best part is that men no longer have to leave village to seek employment and women now need not travel far distances to get a pot of water to quench their thirst! “The waterman of India” now extends his horizons to other five continents to build a strong network of communities in to preserve freshwater all across the world!